Lessons from Kitty Genovese’s Tragic Murder and the Psychology of Taking Action

In the early hours of March 13, 1964, a horrific crime in New York City shocked the nation – not only for its brutality, but for the apparent inaction of those who witnessed it. A young woman named Catherine Susan “Kitty” Genovese was attacked and stabbed outside her apartment while, reportedly, dozens of neighbors looked on and did nothing (Murder of Kitty Genovese – Wikipedia). Public outrage was immense.

As one commentary from that time bitterly observed,

“Anger is directed, not toward the crime, nor the criminal, but toward those who failed to halt the criminal’s actions.”

(See Something. Say Nothing. | Applied Social Psychology (ASP))

This incident became a rallying point for examining a perplexing aspect of human psychology: the bystander effect. Why would so many ordinary people fail to help someone in dire need? In this paper, we will explore the bystander effect and the related concept of diffusion of responsibility, using the Kitty Genovese case as a key example. The goal is to understand these psychological phenomena in plain language, discuss their real-world implications, and ultimately persuade each of us not to be a passive bystander. By the end, you’ll see why taking action in a crisis isn’t just admirable – it’s essential.

What Is the Bystander Effect?

Imagine you see someone collapse on a busy street. There are dozens of people around. Do you rush to help, or do you hesitate, thinking surely someone else will step in? If you’ve ever felt that flicker of hesitation, you’ve experienced the bystander effect. The bystander effect (sometimes called bystander apathy) refers to the phenomenon in which the greater the number of people present, the less likely any one person is to help a person in distress (The Bystander Effect). In other words, a victim might paradoxically be less likely to receive help in a crowded area than in a quiet one.

Psychologists first identified the bystander effect in the 1960s, inspired by the Kitty Genovese tragedy (Bystander effect – Wikipedia). Classic experiments soon confirmed how real this effect is. In one study, researchers Bibb Latané and John Darley found that if people thought they were the only witness to an emergency (like hearing someone have a seizure in the next room), most would quickly try to help. But if they believed others were also present and aware of the crisis, their likelihood of helping dropped sharply (The Bystander Effect). The findings were stark: when participants were alone, about 70% took action to help, but when they believed bystanders were around, only about 40% did (The Bystander Effect). While it seems counter-intuitive – shouldn’t more people mean more help? – the bystander effect shows that our instincts in a group setting can work against us. We take our cues from others’ inaction and assume that maybe intervention isn’t needed, or we simply hope someone else will do something.

Diffusion of Responsibility: The “Someone Else Will Do It” Mentality

One of the major reasons behind the bystander effect is a psychological process known as diffusion of responsibility. This is the sneaky mental trick our brains play when we’re in a crowd. Essentially, the more people around, the less personal responsibility each individual feels. Diffusion of responsibility means that as the number of bystanders increases, the sense of obligation each person feels to act decreases (Bystander effect – Diffusion of Responsibility | Britannica). We subconsciously think, “Why should I be the one to jump in? Someone else here can do it.” (The Bystander Effect). In a group, everyone assumes that someone else will call 911, or that someone else will check on the victim – so no one ends up doing anything.

This isn’t usually a conscious decision to be indifferent; it’s a psychological pass of the buck. We might not even realize we’re doing it. Social psychologists point out that when only one person is present at an emergency, that person knows the responsibility falls entirely on them – and thus they are far more likely to act (Bystander effect – Diffusion of Responsibility | Britannica). However, when others are present, each person’s mind performs a quick calculus: “There are others who could help, so maybe I don’t need to.” The result is that everyone feels less pressure, assuming someone else will take charge (The Bystander Effect). Sadly, if every bystander thinks this way, help never comes. Diffusion of responsibility can be heightened if others in the group appear calmer or if someone who seems more qualified (a police officer, a doctor) is thought to be present (Bystander effect – Diffusion of Responsibility | Britannica). We tell ourselves that our intervention is not necessary or that it’s not our place – a comforting thought that lets us off the hook, but one that can have deadly consequences.

The Kitty Genovese Case: A Wake-Up Call for a Nation

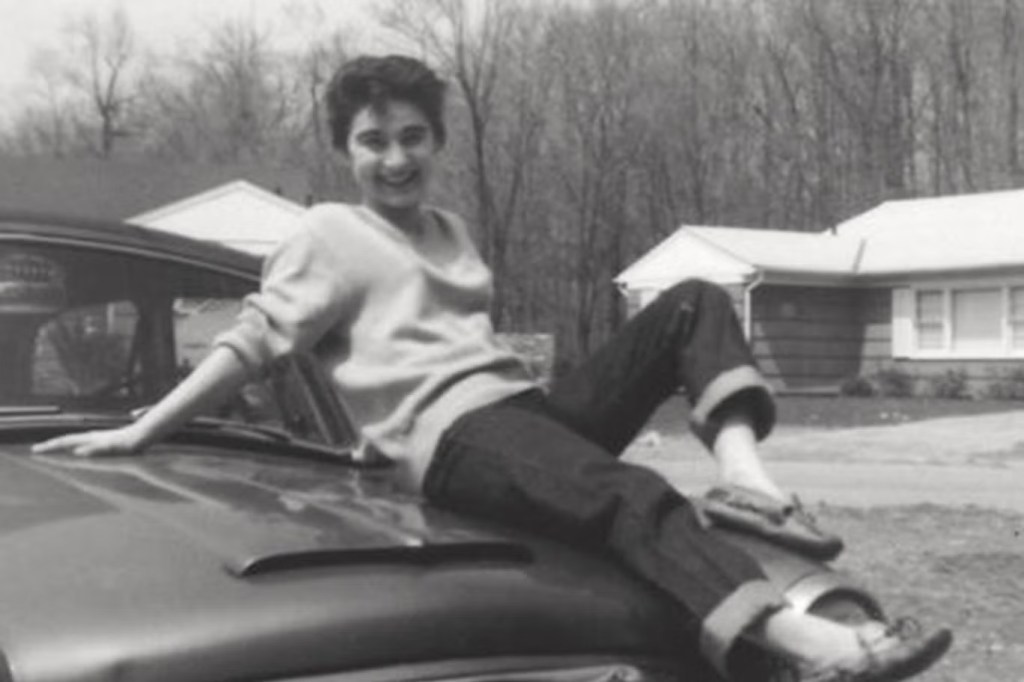

No discussion of the bystander effect is complete without the case that brought it to the world’s attention: the murder of Catherine “Kitty” Genovese. Kitty was a 28-year-old woman living in Kew Gardens, Queens. In the early morning hours of March 13, 1964, as she returned home from work, Kitty was brutally attacked by an assailant (later identified as Winston Moseley) just outside her apartment building (The Bystander Effect). She screamed for help repeatedly as she was stabbed. Lights flickered on in nearby apartment windows. People heard her cries — by some accounts, as many as 37 or 38 neighbors were aware that something terrible was happening (Murder of Kitty Genovese – Wikipedia). Yet, according to the initial news reports, not a single person came to her rescue or even called the police until it was far too late. The attack began at about 3:20 a.m., and only around 3:50 a.m. did one witness finally contact police, by which time Kitty Genovese lay dying (The Bystander Effect).

The New York Times headline later that month captured the public horror: “37 Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police.” The story ignited a national outrage and a lot of soul-searching. How could so many decent, “respectable” people watch a woman be killed and do nothing? Many saw it as a symptom of cold urban indifference – the “apathy” of city dwellers. In fact, the Kitty Genovese murder quickly “symbolized urban apathy [since] 38 people heard her screams but did nothing.” ( Moseley v. Scully, 908 F. Supp. 1120 (E.D.N.Y. 1995) :: Justia) Her case became a staple in psychology textbooks, often cited as the quintessential example of the bystander effect in action (The Bystander Effect).

Psychologists John Darley and Bibb Latané analyzed the witness accounts and concluded that the neighbors’ lack of action was likely due to diffusion of responsibility (Bystander effect – Wikipedia). Each resident figured that someone else must have already called the police or that someone else would interfere. In interviews, some witnesses said they didn’t realize it was a deadly attack – a few thought it might be a drunken argument or a lovers’ quarrel, not realizing the severity of what was happening (The Bystander Effect). Others admitted they assumed someone else had called the authorities. In the end, this tragic misunderstanding of shared responsibility meant that no one acted in time to save Kitty.

It’s important to note that decades later, journalists and researchers discovered that the original story had exaggerations – the number of true witnesses was likely smaller, and at least one person did call the police (albeit after some delay) (The Bystander Effect) (Bystander effect – Wikipedia). The New York Times itself eventually admitted its early reporting was “flawed” and had “grossly exaggerated” the narrative of silent witnesses. But despite these corrections, the core lesson of the Kitty Genovese case endures. Whether it was 38 people or a handful, there’s no doubt that multiple people heard or saw signs of danger, and most failed to act swiftly. The case struck a nerve and became a powerful parable in both psychology and criminal justice circles. It forced us to confront the unsettling reality that good people might freeze or look away when others are around, and it prompted researchers to figure out why.

“Site of the murder of Kitty Genovese in alleyway from Kew Gardens LIRR station to Lefferts Boulevard” by Union Turnpike is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

Above: An alleyway in the Queens neighborhood of Kew Gardens, New York, which became infamous as the site of Kitty Genovese’s 1964 murder. The ordinary appearance of this location belies the tragedy that unfolded here, an event that sparked a national conversation about bystanders and responsibility.

One positive legacy of Kitty Genovese’s case was a push to improve how society handles emergencies. At the time of her attack, there was no centralized 911 number to call for police or ambulance in New York (Murder of Kitty Genovese – Wikipedia). In fact, the outrage over the difficulty witnesses had in contacting help contributed to the creation of the 9-1-1 emergency phone system later in the 1960s (Murder of Kitty Genovese – Wikipedia) (Murder of Kitty Genovese – Wikipedia). In that sense, this tragedy spurred changes that make it easier for bystanders today to report emergencies quickly. But the human element – the choice to make that call or not – is still up to us as individuals.

Real-World Implications: Beyond One Case

The story of Kitty Genovese may be decades old, but the bystander effect and diffusion of responsibility are just as relevant today. We see echoes of this phenomenon in modern events and everyday life. Have you ever scrolled past a video of someone being bullied or hurt, taken by bystanders who didn’t intervene? Sadly, there have been contemporary cases that feel like déjà vu of Genovese’s tragedy – people witnessing someone in danger and failing to help, sometimes even recording the event on their smartphones instead of calling for aid.

For example, in 2017 a group of teenagers in Florida watched and filmed a disabled man drowning in a pond rather than try to help him. They mocked him and did nothing as he struggled and ultimately died. The incident sparked outrage nationwide. Yet, when authorities investigated, they found that no law had been broken by the teens’ inaction. As one Florida prosecutor explained,

“There is no state law that requires a bystander to help or get assistance for someone who is in danger.”

(No Charges For 5 Teens Who Mocked Drowning Man, Didn’t Help | Health News Florida)

In the end, the teens faced no criminal charges for simply standing by, although a public outcry branded their behavior as cruel and “callous,” in the words of the local State Attorney (No Charges For 5 Teens Who Mocked Drowning Man, Didn’t Help | Health News Florida). This case is a chilling reminder that legal systems often do not compel us to act – it truly comes down to moral choice. While we might hope that anyone would call 911 in such a situation, the bystander effect can lead to collective shrugging of shoulders unless one person steps up.

This has real implications for public safety. In an emergency, minutes and seconds count. If everyone assumes someone else will dial the phone or run for help, precious time is lost. Recognizing this, some parts of the world have enacted laws to fight bystander apathy. For instance, the Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms of Quebec (Canada) imposes a legal duty:

“Every person must come to the aid of anyone whose life is in peril, either personally or calling for aid, unless it involves danger to himself or a third person, or he has another valid reason.”

(Bystander effect – Wikipedia)

Similarly, countries like Brazil and Germany have laws making it a crime to knowingly fail to help in an emergency when you safely can (Bystander effect – Wikipedia). These laws send a strong message that society expects us to take action, not stand idle when someone’s life is at stake.

In the United States, the approach has been a bit different. Rather than require action, most U.S. states have Good Samaritan laws – these laws don’t force bystanders to intervene, but they protect those who do choose to help. For example, a typical Good Samaritan law will ensure that if you try to aid an injured person in good faith (and perhaps accidentally make things worse), you won’t be held legally liable for harm caused in the attempt. The intent is to remove the fear of being sued as a barrier to helping. However, there are very few U.S. laws that require you to act. Outside of specific situations (like mandatory reporting laws for certain professionals, or rare local ordinances), it’s largely up to individual conscience.

What does all this mean? It means that in most cases the choice to be a hero or a bystander is yours alone – not a legal obligation, but a moral one. The Genovese case and others show that countless factors can influence that choice: the size of the crowd, ambiguity about what’s happening, fear of getting hurt or of “doing the wrong thing,” or even simply being young and not understanding the stakes. But while psychology explains why the bystander effect happens, it doesn’t excuse it. Understanding these forces is the first step toward resisting them. We have to remember that each of us is accountable for what we do or don’t do in critical moments. As the saying goes in the security and law enforcement world, “If you see something, say something.” A simple phone call to report a crime or get medical help can literally save a life. We should never assume it’s somebody else’s problem.

Breaking the Silence: A Call to Action

It’s easy to read about the bystander effect and feel disheartened. After all, none of us wants to think we’d be the person who walks by or stays silent. The encouraging news is that awareness is a powerful antidote. Psychologists suggest that simply knowing about the bystander effect can help us overcome it (The Bystander Effect). When you recognize that little voice in your head saying “someone else will handle this,” you can consciously shut it down and decide “No – I will do something.”

So, what can you do to break the pattern and be an active helper in a crisis? Here are a few practical steps and reminders:

- Take Initiative to Call 911: Never assume someone else already did. In emergencies, it’s always better to have multiple calls than none. The moment you suspect something is wrong – an accident, a fire, an assault – pick up the phone. Emergency operators would rather get duplicate reports than no report at all. Your call could be the fastest way to get professional help to the scene.

- Make It Personal: If you are in a crowd, you can counter diffusion of responsibility by making a personal appeal. Either take charge yourself or single out one person for assistance – for example, point to someone specific and say “You, please help me with this!” This approach eliminates the ambiguity about who should act. Research has shown that when someone feels personally asked to help, they are much more likely to do so, because the responsibility is no longer diffused among everyone present.

- Assess Safety, But Don’t Hide Behind It: It’s important to keep yourself safe – you shouldn’t jump into a situation that puts your own life in unreasonable danger. However, most acts of help (like making a phone call, shouting for help, or offering basic first aid) can be done without significant risk. Don’t use safety as a convenient excuse for doing nothing. If direct intervention is dangerous (say, a violent crime in progress), then help indirectly by calling authorities immediately or finding someone with the appropriate training (security guard, etc.). Remember, calling for help is itself a form of helping.

- Practice Empathy – Imagine If It Were You or Your Loved One: One way to spur yourself to action is to put yourself in the shoes of the victim. If you were the person bleeding on the street or crying for help, how desperately would you want someone to stop and assist you? If it were your family member being attacked or having a medical emergency, wouldn’t you pray that bystanders wouldn’t just gawk? Sometimes flipping the perspective from “What if I embarrass myself by getting involved?” to “How would I feel if I needed help and no one helped me?” can trigger the empathy and courage needed to act.

Finally, spread the word about these concepts. If you discuss the bystander effect and how to beat it with friends and family, you’re helping create a culture of active bystanders. Some communities and organizations now offer bystander intervention training – for example, programs that teach people how to safely intervene to stop bullying, sexual harassment, or public assaults. The more people understand this psychology, the more likely they are to override it. We should treat stepping up to help as a proud norm, not as an extraordinary exception.

Conclusion: Be the One Who Helps

The murder of Kitty Genovese was a tragedy that revealed an uncomfortable truth: Doing nothing can be just as harmful as doing the wrong thing (Latané & Darley, 1968). We’ve learned that the bystander effect and diffusion of responsibility are powerful influences on human behavior – but they are not destiny. Each of us has the ability to recognize these forces and choose to act differently. Whether it’s calling 911 when we witness an accident, intervening when we hear a cry for help, or simply checking on a person who looks unwell, our actions as bystanders can save lives (Fischer et al., 2011).

It’s not an exaggeration to say that you might be the difference between life and death for someone in crisis. One person taking responsibility can spur others to follow. Courage is contagious. When you step forward, you not only help the victim, but also inspire and give permission for others to assist as well – breaking the spell of silence and inaction (Darley & Latané, 1970).

As Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel stated,

“What hurts the victim most is not the cruelty of the oppressor, but the silence of the bystander.”

(Wiesel, 1986).

And as British philosopher Edmund Burke is often quoted,

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.”

(Burke, n.d.)

These words are more than just history—they are a warning. Inaction enables harm. Silence can be as dangerous as the wrongdoing itself.

So ask yourself: When the moment comes, will you be a bystander, or will you be the one who steps forward? The world doesn’t need more passive observers—it needs people willing to help (Staub, 2015).

The next time you hear a cry for help, witness an injustice, or see someone in need—be the one who acts. Be the one who makes the call. Be the one who refuses to stand by.

Because in the end, doing nothing is still a choice. And sometimes, it’s the most dangerous choice of all.

References:

- Wikipedia: “Bystander effect.” Wikipedia (2023). en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bystander_effect.

- Wikipedia: “Murder of Kitty Genovese.” Wikipedia (2023). en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murder_of_Kitty_Genovese.

- Fenstermacher, E., & Scott, E. “Stand By or Stand Up: Exploring the Biology of the Bystander Effect.” Biological Psychiatry, vol. 89, no. 3 (2021): e19–e21. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8692770.

- Verywell Mind: Kendra Cherry. “How Diffusion of Responsibility Affects Group Behavior.” VerywellMind.com, 13 Oct 2022. http://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-diffusion-of-responsibility-2795095.

- Verywell Mind: Kendra Cherry. “How to Overcome the Bystander Effect.” VerywellMind.com, 5 Nov 2020. http://www.verywellmind.com/how-to-overcome-the-bystander-effect-2795559.

- Ethics Unwrapped (Univ. of Texas): “Diffusion of Responsibility.” ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/glossary/diffusion-of-responsibility.

- IAED Journal: Heather Darata. “Adoption of 911.” iaedjournal.org/adoption-of-911.

- Wikipedia: “Good Samaritan law.” Wikipedia (2023). en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Good_Samaritan_law.Latané, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(4), 377–383.

- “See Something, Say Nothing” (See Something. Say Nothing. | Applied Social Psychology (ASP))

- Associated Press – Florida teens bystander case (June 24, 2018)

- Burke, E. (n.d.). The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing. Retrieved from ChrisHeath.us

- Wiesel, E. (1986). Nobel Lecture. Retrieved from NobelPrize.org